Source: Harvard Business Review

Source: Harvard Business Review

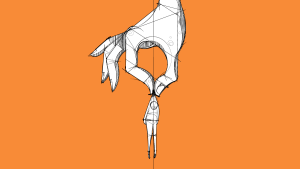

Micromanaging is a hard habit to break. You may downplay your propensities by labeling yourself a “control freak” or by claiming that you just like to keep close tabs on your team, but those are poor excuses for excessive meddling. What can you do to give your people the space they need to succeed and learn? How should you prioritize what matters? And how do you get comfortable stepping back?

What the Experts Say

If you’re the kind of boss who lasers in on details, prefers to be cc’ed on emails, and is rarely satisfied with your team’s work, then—there’s no kind way to say this—you’re a micromanager. “For the sake of your team, you need to stop,” says Muriel Maignan Wilkins, coauthor of Own the Room and managing partner of Paravis Partners, an executive coaching and leadership development firm. “Micromanaging dents your team’s morale by establishing a tone of mistrust—and it limits your team’s capacity to grow,” she says. It also hampers your ability to focus on what’s really important, adds Karen Dillon, author of theHBR Guide to Office Politics. “If your mind is filled with the micro-level details of a number of jobs, there’s no room for big picture thoughts,” she says. As hard as it may be to change your ways, the “challenge is one that will pay off in the long run,” says Jennifer Chatman, a professor at UC Berkeley’s Haas School of Business. “There may be a few failures as your team learns to step up, but ultimately they will perform much, much better with greater accountability and less interference.”

Here are some pointers on how to let go.

Reflect on your behavior

The first step is to develop an awareness of why you micromanage. “You need to understand where this is coming from,” says Dillon. “Most likely it’s because of some insecurity—you’re afraid it will reflect badly on you if your team doesn’t do something exactly the way you would do it or you’re worried you’ll look out of touch if you’re not immersed in the details, so you overcompensate,” she says. Wilkins recommends “asking yourself: what excuses am I using to micromanage?” Common justifications include: “It will save time if I do it myself.” Or “Too much is at stake to allow this to go wrong.” She advises focusing on “the reasons why you should not micromanage”—it’s bad for your team as they don’t learn and grow—“and the benefits you’d derive if you stopped,” chiefly more time to do your own job.

Get feedback

“Often there is a significant disconnect between what leaders intend and what the team is actually experiencing,” says Chatman. You may merely suspect you have a problem while your team members are already annoyed by your constant hovering “Feedback is essential to see how significant the issue is.” To get a handle on what your direct reports really thinkand whether it lines up with your intentions, she recommends “undertaking a cross-evaluation assessment.” Gather confidential data from your people—or better yet, have a third party do it—and aggregate those results so employees know you can’t find out exactly who said what. What you hear may be sobering, “but it’s critical to understanding the broader patterns and reactions and the impact [your micromanaging has] on your team,” she says.

Prioritize what matters—and what doesn’t

“A good manager trains and delegates,” says Dillon, and you can’t do that if you’re taking on everything—regardless of how important the task is—yourself. Start by determining what work is critical for you to be involved in (e.g. strategic planning) and what items are less important (e.g. proofreading the presentation). Wilkins suggests looking at your to do list “to determine which low-hanging fruit you can pass on to a team member.” You should also highlight the priorities on your list, meaning “the big ticket items where you truly add value,” and ensure you are “spending most of your energy” on those, she adds. Remember, says Chatman, “Micromanaging displaces the real work of leaders, which is developing and articulating a compelling and strategically relevant vision for your team.”

Talk to your team

Once you’ve determined your priorities, the next step is communicating them to your team, says Dillon. “Have a conversation about the things that really matter to you—the things that they’ll need to seek your guidance and approval on—so your direct reports can get ahead of your anxiety,” she says. Tell them how you’d like to be kept in the loop and how often they should provide status updates. “Be explicit with your direct reports about the level of detail you will engage in,” adds Wilkins. At the same time, enlist their help in making sure you don’t fall back into your old micromanaging ways. Chatman suggests: “Tell them you are trying to work on this” and ask targeted questions such as: How can I help you best? Are there things I can do differently? Are our overall objectives clear to you and do you feel you have the support and resources to accomplish them?

Step back slowly

Fighting your micromanaging impulses might be hard at first so pull back slowly. You need to get comfortable, too. “Do a test run on a project that is a bit less urgent and give your team full accountability and see how it goes,” Chatman says. “Recognize that your way is not the only, or even necessarily, the best way.” The acid test of leadership, she says, “is how well the team does when you’re gone.” Another way to ease out of micromanaging is to discretely seek feedback from other coworkers about how your team is operating, says Dillon. “Ask a colleague you trust: ‘How’s that project going?’” The answer will provide valuable information, says Dillon. “You may feel better knowing that everything is fine, or you may realize you pulled back too much.” In the latter case, you need to “find a way [to support the work] that doesn’t involve peering over your employees’ shoulders.”

Build trust

Because your team members are used to you not trusting them, they may want to come to you for approval before taking charge of a project. “Acknowledge this is a growth opportunity for the person and say that you know in your heart of hearts he or she will rise to the challenge,” says Dillon. This is more than a pep talk. You’re in effect “giving your employee the psychological power to lead.” Making sure your team members know you trust them and have faith in their abilities is actually “very simple,” says Wilkins. “Tell them so. Say, ‘I fully trust you can make this decision.’” And then, “walk the talk,” she says. Don’t excessively scrutinize. Don’t insist on being cc’d on every email. And don’t renege on your vote of confidence. “Let them do it and don’t back pedal and change everything they did.”

And if things don’t go exactly as you’d like, try your hardest not to overact. Take a breath; go for a walk; do whatever you need to do to come “back from that agitated micro-managerial moment,” says Dillon. After all, does it really matter if the memo isn’t formatted exactly to your liking? “For most things, nothing is so bad it can’t be corrected.”

Know your employees’ limitations

“Some people will over correct by pulling away too much; but it’s smart to give appropriate support,” says Dillon. “Talk about how you will help them problem solve and how you’ll support them” even if you’re not deeply involved in a particular project or task. At the same time, keeping a closer eye on certain projects or certain employees is sometimes warranted, she adds. If “your report is junior,” say, or “not yet ready to be trusted,” you will need to keep close tabs on her work. Similarly, says Wilkins, “when the deliverable is urgent and high stakes” it may make sense to intervene or ask to be kept regularly apprised of things. “In this case, it’s helpful if you explain to the person why you are being so hands on,” she says. “You should also give feedback to the employee and coach them, so they can complete the task on their own over time.”

Principles to Remember

Do:

- Ask yourself why you micromanage and reflect on your need for control

- Refine your to do list by prioritizing the tasks and projects that matter most to you

- Talk to your team about how you’d like to be kept apprised of their progress

Don’t:

- Renege on your vote of confidence—tell your reports you trust them and let them do their jobs

- Overact when things don’t go exactly as you’d like them to—take a breath and figure out a way to correct the situation if it’s truly necessary

- Go too far—you don’t want to become a hands-off boss